Repair and Reconciliation

Contents

18.4. Repair and Reconciliation#

The idea of repair (or reconciliation) has shown up a couple times already, both in the role of shame in child development, and in the Enforcing Social Norms: The Morality of Public Shaming paper. Let’s look more at what a repair might or might not look like.

18.4.1. Limits of Reconciliation#

When we think about repair and reconciliation, many of us might wonder where there are limits. Are there wounds too big to be repaired? Are there evils too great to be forgiven? Is anyone ever totally beyond the pale of possible reconciliation? Is there a point of no return?

One way to approach questions of this kind is to start from limit cases. That is, go to the farthest limit and see what we find there by way of template, then work our way back toward the everyday. Let’s look at two contrasting limit cases: one where philosophers and cultural leaders declared that repairs were possible even after extreme wrongdoing, and one where the wrongdoers were declared unforgivable.1

Nuremberg Trials#

After the defeat of Nazi Germany, prominent Nazi figures were put on trail in the Nuremberg Trials. These trials were a way of gathering and presenting evidence of the great evils done by the Nazis, and as a way of publicly punishing them. We could consider this as, in part, a large-scale public shaming of these specific Nazis and the larger Nazi movement.

Some argued that there was no type of reconciliation or forgiveness possible given the crimes committed by the Nazis. Hannah Arendt argued that not even any punishment that could ever be sufficient:

The Nazi crimes, it seems to me, explode the limits of the law; and that is precisely what constitutes their monstrousness. For these crimes, no punishment is severe enough. It may well be essential to hang Göring, but it is totally inadequate.

See also:

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil by Hannah Arendt

Truth and Reconciliation Commission#

In South Africa, when the oppressive and violent racist apartheid system ended, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu set up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The commission gathered testimony from both victims and perpretrators of the violence and oppression of apartheid. We could also consider this, in part, a large-scale public shaming of apartheid and those who hurt others through it. Unlike the Nuremberg Trials, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission gave a path for forgiveness and amnesty to the perpretrators of violence who provided their testimony.

See also:

18.4.2. Steps for Repentance#

For when reconciliation is possible, what would it look like?

In the article Famous abusers seek easy forgiveness. Rosh Hashanah teaches us repentance is hard. by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, she outlines a set of steps for “repentance” needed for someone to have their relationship with others repaired:

“The bad actor must own the harm perpetrated, ideally publicly”

“They must do the hard internal work to become the kind of person who does not harm in this way — which is a massive undertaking, demanding tremendous introspection and confrontation of unpleasant aspects of the self”

“They must make restitution for harm done, in whatever way that might be possible”

“Then — and only then — they must apologize sincerely to the victim”

“Lastly, the next time they are confronted with the opportunity to commit a similar misdeed, they must make a different, better choice”

18.4.3. Repair Example#

On February 6, 2022, Jeremy Schneider became the Twitter “main character of the day” for posting the following Tweet, which was widely condemned as being mean and not understanding of other people’s experiences:

Fig. 18.1 Jeremy Schneider’s Tweet#

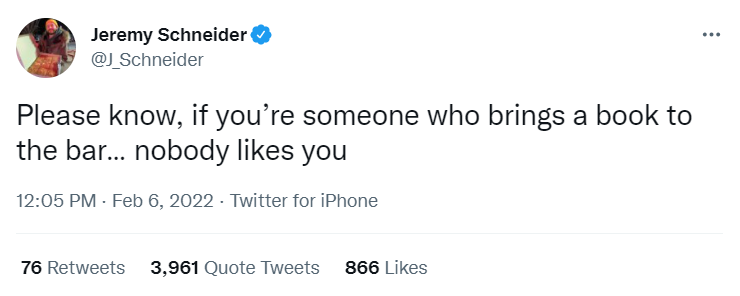

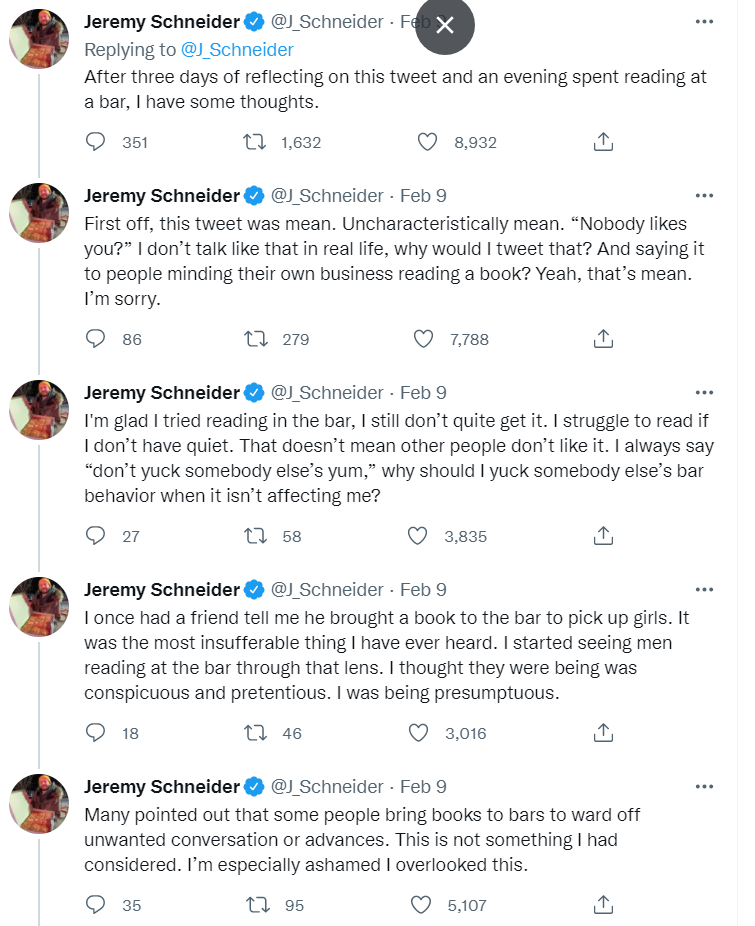

In what was an unusual turn of events for a Twitter “main character of the day,” Jeremy Schneider later made an apology that was mostly accepted by the Twitter users who had criticized his Tweet:

Fig. 18.2 Part 1 of Jeremy Schneider’s apology#

Fig. 18.3 Part 2 of Jeremy Schneider’s apology#

18.4.4. Reflection questions#

Do you think there are situations where reconciliation is not possible?

What would reconciliation look like (if possible), when a social media platform is used in a genocide (see: Meta urged to pay reparations for Facebook’s role in Rohingya genocide)

Does Jeremy Schneider’s apology cover the five steps of repentance listed by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg?

Pick a situation where someone is being publicly shamed. Who is responsible for accepting or rejecting their apology/repentance?

Pick a social media platform and a situation where someone is being publicly shamed. What might that person do to try to repair or reconciliation after the public shaming?

Pick a social media platform. In what ways does that platform make it difficult to repair or reconciliation after public shaming?

- 1

We give these two examples to illustrate how important it is to appreciate the breadth of views on this incredibly difficult question, not to imply that one view or the other is preferable. The Nuremberg Trials or the Truth and Reconcilitiation Commission are both attempts at responding to great evils, and we believe it is important to understand different views of people who suffered. So take your time to think through your intuitions about these limit cases, and research different perspectives on these events (and other atrocities), and then work your way back to the everyday context of social media posting.